Apple and Google, who last Friday jointly | announced new capabilities for contact tracing coronavirus carriers at scale, released a new statement yesterday clarifying that no government would tell them what to do. Or, to put it in the gentler terms conveyed by CNBC:

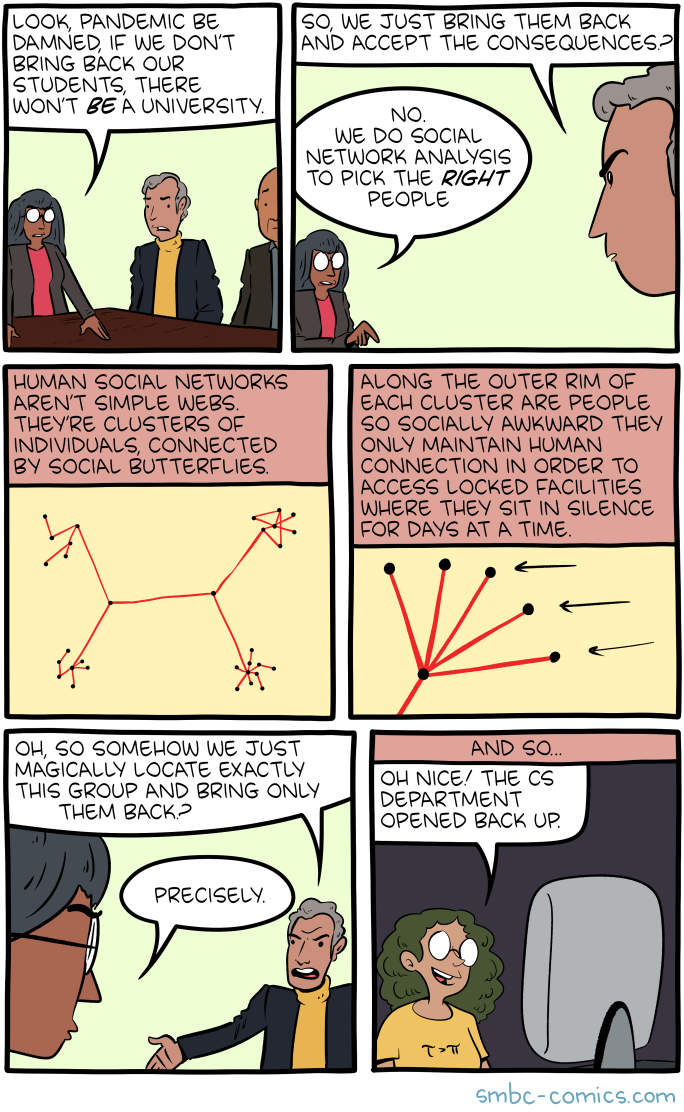

Apple and Google, normally arch-rivals, announced on Friday that they teamed up to build technology that enables public health agencies to write contact-tracing apps. The partnership is being closely watched: The two Silicon Valley giants are responsible for the two dominant mobile operating systems globally, iOS and Android, which together run almost 100% of smartphones sold, according to data from Statcounter…The fact that the apps work best when a lot of people use them have raised fears that governments could force citizens to use them. But representatives from both companies insist they won’t allow the technology to become mandatory…

The way the system is envisioned, when someone tests positive for Covid-19, local public health agencies will verify the test, then use these apps to notify anybody who may have been within 10 or 15 feet of them in the past few weeks. The identity of the person who tested positive would never be revealed to the companies or to other users; their identity would be tracked using scrambled codes on phones that are unlocked only when they test positive. Only public health authorities will be allowed access these APIs, the companies said. The two companies have drawn a line in the sand in one area: Governments will not be able to require its citizens to use contact-tracing software built with these APIs — users will have to opt-in to the system, senior representatives said on Monday.

The reality that tech companies, particularly the big five (Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Facebook), effectively set the rules for their respective domains has been apparent for some time. You see this in debates about what content to police on Facebook or YouTube, what apps to allow and what rules to apply to them on iOS and Android, and the increasing essentiality of AWS and Azure to enterprise. What is critical to understand about this dominance is why it arises, why current laws and regulations don’t seem to matter, and what signal it is that actually drives big company decision-making.

Scale and Zero Marginal Costs

Tech, from the very beginning of Silicon Valley, has been about scale in a way few other industries have ever been: silicon, the core element in computer chips, is basically free, which meant the implication of zero marginal costs — and relatedly, the importance of investing in massive fixed costs — has been at the core of business from the time of Fairchild Semiconductor. From The Intel Trinity by Michael Malone:

What Noyce explained and Sherman Fairchild eventually believed was that by using silicon as the substrate, the base for its transistors, the new company was tapping into the most elemental of substances. Fire, earth, water, and air had, analogously, been seen as the elements of the universe by the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers. Noyce told Fairchild that these basic substance — essentially sand and metal wire — would make the material cost of the next generation of transistors essentially zero, that the race would shift to fabrication, and that Fairchild could win that race. Moreover, Noyce explained, these new cheap but powerful transistors would make consumer products and appliances so inexpensive that it would soon be cheaper to toss out and replace them with a more powerful version than to repair them.

This single paragraph remains the most important lens with which to understand technology. Consider the big 5:

- Apple certainly incurs marginal costs when it comes to manufacturing devices, but those devices are sold with massively larger margins than Apple’s competitors thanks to software differentiation; software has huge fixed costs and zero marginal costs. That differentiation created the App Store platform, where developers differentiate Apple’s devices on Apple’s behalf without Apple having to pay them; in fact, Apple takes 30% of their revenue.

- Microsoft built its empire on software: Windows created the same sort of platform as iOS, while Azure is first-and-foremost about spending an overwhelming amount of money on hardware and then charging companies to rent it (followed by software differentiation with platform services); Office, meanwhile, has shifted from the very profitable model of writing software and then duplicating it endlessly for license fees to the extremely profitable model of writing software and then renting it endlessly for subscription payments.

- Google spends massively on software, data centers, and data collection to create virtuous cycles where users access its servers to gain access to 3rd-party content, whether that be web pages, videos, or ad-supported content, which incentivizes suppliers to create even more content that Google can leverage to make itself better and more valuable to users.

- AWS is the same model as Azure; Amazon.com has invested massive amounts of money on logistic capabilities — with huge marginal costs, to be clear, which has always made Amazon unique — to create an indispensable platform for suppliers and 3rd-party merchants.

- Facebook, like Google, spends massively on software, data centers, and data collection to create virtuous cycles where users access its servers to gain access to third-party content, but the real star of the show is first-party content that is exclusive to Facebook — making it incredibly valuable — and yet free to obtain.

None of the activities I just detailed are illegal by any traditional reading of antitrust law (some of Google’s activities and Apple’s App Store policies come closest). The core problem are the returns to scale inherent in a world of zero marginal costs — first in the case of chips, and then in the case of software — that result in bigger companies becoming more attractive to both users and suppliers the larger they become, not less.

Understanding Versus Approval

Facebook, earlier this year, took this reality to its logical conclusion, at least as far as its battered image in the media was concerned. CEO Mark Zuckerberg, on the company’s earnings call in January, said:

We’re also focused on communicating more clearly what we stand for. One critique of our approach for much of the last decade was that because we wanted to be liked, we didn’t always communicate our views as clearly because we were worried about offending people. So this led to some positive but shallow sentiment towards us and towards the company. And my goal for this next decade isn’t to be liked, but to be understood. Because in order to be trusted, people need to know what you stand for.

So we’re going to focus more on communicating our principles, whether that’s standing up for giving people a voice against those who would censor people who don’t agree with them, standing up for letting people build their own communities against those who say that the new types of communities forming on social media are dividing us, standing up for encryption against those who say that privacy mostly helps bad people, standing up for giving small businesses more opportunity and sophisticated tools against those who say that targeted advertising is a problem, or standing up for serving every person in the world against those who say that you have to pay a premium in order to really be served.

These positions aren’t always going to be popular, but I think it’s important for us to take these debates head-on. I know that there are a lot of people who agree with these principles, and there are a whole lot more who are open to them and want to see these arguments get made. So expect more of that this year.

The social network, for once, was ahead of the curve, as the coronavirus showed just how critical it was to allow the free flow of information, something I detailed in Zero Trust Information:

The implication of the Internet making everyone a publisher is that there is far more misinformation on an absolute basis, but that also suggests there is far more valuable information that was not previously available:

It is hard to think of a better example than the last two months and the spread of COVID-19. From January on there has been extensive information about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 shared on Twitter in particular, including supporting blog posts, and links to medical papers published at astounding speed, often in defiance of traditional media. In addition multiple experts including epidemiologists and public health officials have been offering up their opinions directly.

Moreover, particularly in the last several weeks, that burgeoning network has been sounding the alarm about the crisis hitting the U.S. Indeed, it is only because of Twitter that we knew that the crisis had long since started (to return to the distribution illustration, in terms of impact the skew goes in the opposite direction of the volume).

The Problem With Experts

If I can turn solipsistic for a moment, while preparing that piece, I warned a friend that it would be controversial, and he couldn’t understand why. In fact, though, I turned out to be right: lots of members of the traditional media didn’t like the piece at all, not because I attacked the traditional media — which I mostly didn’t, and in fact relied on its reporting, as I consistently do on Stratechery — but because I dared to suggest that a world without gatekeepers had upside, not just downside.

I went further two weeks ago in Unmasking Twitter, arguing that the media’s overreliance on experts was precisely why social media should not be censored:

It sure seems like multiple health authorities — the experts Twitter is going to rely on — have told us that masks “are known to be ineffective”: is Twitter going to delete the many, many, many tweets — some of which informed this article — arguing the opposite?

The answer, obviously, is that Twitter won’t, because this is another example of where Twitter has been a welcome antidote to “experts”; what is striking, though, is how explicitly this shows that Twitter’s policy is a bad idea, not just because it allows countries like China to indirectly influence its editorial decisions, but also because it limits the search for truth.

Interestingly, this self-reflective piece by Peter Kafka, appears to agree with at least the first part of that argument:

As we head into the next phase of the pandemic, and as the stakes mount, it’s worth looking back to ask how the media could have done better as the virus broke out of China and headed to the US. Why didn’t we see this coming sooner? And once we did, why didn’t we sound the alarm with more vigor?

If you read the stories from that period, not just the headlines, you’ll find that most of the information holding the pieces together comes from authoritative sources you’d want reporters to turn to: experts at institutions like the World Health Organization, the CDC, and academics with real domain knowledge.

The problem, in many cases, was that that information was wrong, or at least incomplete. Which raises the hard question for journalists scrutinizing our performance in recent months: How do we cover a story where neither we nor the experts we turn to know what isn’t yet known? And how do we warn Americans about the full range of potential risks in the world without ringing alarm bells so constantly that they’ll tune us out?

What is striking about Kafka’s assessment — which to be clear, should be applauded for its self-awareness and honesty — is the degree to which it effectively accepts the premise that journalists ought not think for themselves, but rather rely on experts.

But when it came to grappling with a new disease they knew nothing about, journalists most often turned to experts and institutions for information, and relayed what those experts and institutions told them to their audience.

Again, I appreciate the honesty; it backs up my argument in Unmasking Twitter that this reflected the traditional role the media played:

In the analog world, politicians and experts needed the media to reach the general population; debates happened between experts, and the media reported their conclusions. Today, though, politicians and experts can go direct to people — note that I used nothing but tweets from experts above. That should be freeing for the media in particular, to not see Twitter as opposition, but rather as a source to challenge experts and authority figures, and make sure they are telling the truth and re-visiting their assumptions.

This, notably, is another area where the biggest tech companies are far ahead.

The Waning of East Coast Media

Yesterday the New York Times wrote an article entitled, The East Coast, Always in the Spotlight, Owes a Debt to the West:

The ongoing effort of three West Coast states to come to the aid of more hard-hit parts of the nation has emerged as the most powerful indication to date that the early intervention of West Coast governors and mayors might have mitigated, at least for now, the medical catastrophe that has befallen New York and parts of the Midwest and South.

Their aggressive imposition of stay-at-home orders has stood in contrast to the relatively slower actions in New York and elsewhere, and drawn widespread praise from epidemiologists. As of Saturday afternoon, there had been 8,627 Covid-19 related deaths in New York, compared with 598 in California, 483 in Washington and 48 in Oregon. New York had 44 deaths per 100,000 people. California had two.

But these accomplishments have been largely obscured by the political attention and praise directed to New York, and particularly its governor, Andrew M. Cuomo. His daily briefings — informed and reassuring — have drawn millions of viewers and mostly flattering media commentary…

This disparity in perception reflects a longstanding dynamic in America politics: The concentration of media and commentators in Washington and New York has often meant that what happens in the West is overlooked or minimized. It is a function of the time difference — the three Pacific states are three hours behind New York — and the sheer physical distance. Jerry Brown, the former governor of California, a Democrat, found that his own attempts to run for president were complicated by the state where he worked and lived.

Jerry Brown ran for President in 1976, 1980, and 1992; this analysis was likely correct then — before the Internet. What seems more likely, now, though, is that this article takes a dose of my previous solipsism and doubles down: the New York Times may not pay particular attention to the West, but that is not necessarily reflective of the rest of the world.

Critically, it is not reflective of tech companies: what has been increasingly whitewashed in the story of California and Washington’s success in battling the coronavirus is the role tech companies played: the first work-from-home orders started around March 1st, and within a week nearly all tech companies had closed their doors; local governments followed another week later.

This action by local governments was, to be clear, before the rest of the country, and without question saved thousands of lives; it should not be forgotten, though, that executives who listened not to the media but primarily to social and non-traditional media were the furthest ahead of the curve. In other words, it increasingly doesn’t matter who or what the media covers, or when: success comes from independent thought and judgment.

Coronavirus Clarity

This gets at why the biggest news to come out of Apple and Google’s announcement is, well, the lack of it. Specifically, we have a situation where two dominant companies — a clear oligopoly — are creating a means to track civilians, and there is no pushback. Moreover, it is baldly obvious that the only obstacle to this being involuntary is not the government, but rather Apple and Google. What is especially noteworthy is that the coronavirus crisis is the one time we might actually wish for central authorities to overcome privacy concerns, but these companies — at least for now — won’t do it.

This is, in other words, the instantiation of Zuckerberg’s declaration that Facebook — and, apparently, tech broadly — would henceforth seek understanding, not necessarily approval. Apple and Google are leaning into their dominant position, not obscuring it or minimizing it. And, because it is about the coronavirus, we all accept it.

It is, in fact, a perfect example of what I wrote about last week:

At the same time, I think there is a general rule of thumb that will hold true: the coronavirus crisis will not so much foment drastic changes as it will accelerate trends that were already happening. Changes that might have taken 10 or 15 years, simply because of the stickiness of the status quo, may now happen in far less time.

This seems likely to be the case when it comes to tech dominance, or at least the acceptance thereof. The truth is we have been living in a world where tech answers to no one, including the media, but we have all — both tech and the media — pretended otherwise. Those days seem over.

The truth, though, is that this is, unequivocally, a good thing. To have pretended otherwise — for Facebook to have curried favor, or Apple to pretend like it didn’t have market power — was a convenient lie for everyone involved. The media was able to feel powerful, and tech companies were able to consolidate their position without true accountability.

What we desperately need is a new conversation that deals with the world as it will be and increasingly is, not as we delude ourselves into what once was and wish still were. Tech companies are powerful, but antitrust laws, formulated for oil and railroad companies, don’t really apply. East coast media may dominate traditional channels, but those channels are just one of many on social media, all commoditized in personalized feeds. Centralized governments, predicated on leveraging scale, may be no match for either hyperscale tech companies or, on the flipside, the micro companies that are unlocked by the existence of platforms.

I don’t have all of the answers here, although I think new national legislative approaches, built on the assumption of zero marginal costs, in conjunction with a dramatic reduction in local regulatory red-tape, gets at what better approaches might look like. Figuring out those approaches, though, means clarity about where we actually are; for that, it turns out, a virus, so difficult to understand, is tremendously helpful.